Keynote

STUDENTS AT THE CENTER:

APPRECIATING THE VALUE OF ORAL COMMUNICATION

NACC Keynote, April 2014

Arizona State University-West Campus

Kathleen J. Turner

Davidson College

I am delighted with Bonnie’s theme of “Students at the Center,” for it is both apt and evocative. Students come to our centers, and they are the center of our mission. Our tutors, peer consultants, coaches, advisors, and mentors are at the center of accomplishing that mission. And communication centers exist to empower students.

I hope to follow in the same evocative vein with my subtitle, “appreciating the value of oral communication”—both in the sense of how worthwhile oral communication is, and in the sense of how the value of oral communication grows exponentially. After all, as Isocrates noted a couple thousand years ago, “None of that which is done with intelligence is done without the aid of speech.” He continued, "to become eloquent is to activate one's humanity, to apply the imagination, and to solve the practical problems of human living." Hey, that’s value!

In particular, I’d like to address one of the questions Bonnie included in her call for this conference: Why are communication centers important and relevant to student success?

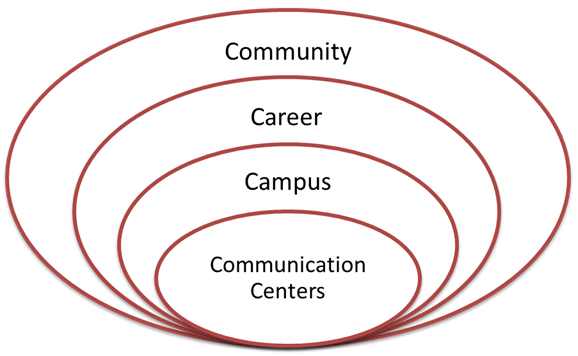

In doing so, let’s explore how we can appreciate the value of students at the center, on campus, for careers, and in the community (see graphic below).

I. Our centers are centered on our campuses.

Our primary mission is to facilitate the educational process for our students, by working directly with students and by working with faculty on how to design, assign, and assess oral communication. And oh, how they need us! They’ve received a fair amount of instruction and practice in writing, and many of them still are (shall we say) challenged! But think about it: few of them have received any instruction and practice in speaking. The attitude seems to be that we’ve been talking since we were knee-high to grasshoppers, so we really shouldn’t need any special instruction in it!

And yet faculty regularly evaluate not only students’ knowledge of the course material, but also their overall intelligence and their future potential, based on how articulate they are.

Research consistently shows that “communication apprehension and hesitancy to communicate undermine academic and professional performance.” Conversely, better communicators are better students: more articulate, more confident students have higher scores on college entrance exams, higher GPAs, more positive attitudes toward school, and better college retention rates.

That’s the value of better communication overall. Research specifically on peer tutoring, including communication centers, demonstrates that such assistance results in higher GPAs and higher retention rates --and we need more such assessments! [There’s a brand-new Communication Centers Journal, and I know editor Ted Sheckels would love to have good stuff like this to publish!]

Incorporating oral communication activities in the classroom: it increases students’ motivation by making them active participants in the learning process, which creates a better understanding of the material in the course.

As no lesser light than Ernest L. Boyer, past president of the Carnegie Foundation, argues that “As undergraduates [and graduates!] develop their linguistic skills, they hone the quality of their thinking and become intellectually and socially empowered.” Student engagement and understanding increase when a course uses significant oral com assignments—when, as Bob Weiss argued, faculty “let students in on the educational act.”

Those of us in communication centers value “speaking to learn, learning to speak”—because we understand that oral communication is a process of intellectual engagement. As Tom Steinfatt observed, “the cognitive act of message formation and the behavioral act of message delivery . . . changes the way a student thinks about any issue, problem or topic area. . . . The act of creating and communicating a message is at the heart of the educational experience” (emphases added).

By and large, students seem to recognize the value of oral communication in the educational process: At the University of Mary Washington, did students in the speaking intensive courses request more opportunities to write or to be tested? No—but they did ask for more opportunities to speak. When the Graduate School of Management at Cornell offered classes in either writing or speaking, not enough students signed up for the writing course for it to be offered—but “students jumped at the speech class.”

Is it because they’re all chomping at the bit to speak? No: we all know that some folks are terrified of public speaking. You’ve probably heard the old Seinfeld gag about how, at a funeral, most people would rather be the one in the coffin than the one giving the eulogy! No, it’s because most students understand that the ability to be articulate is critical to their success.

But what does it mean to be articulate? Too many people think it’s like the title of David Sedaris’s book: “me talk pretty one day.” I’m sure you’ve had experiences like those of Deanna Dannels, whose colleagues in other disciplines wanted those of us in communication to “just fix those delivery problems!” Well, bless their hearts.

Let me share a story about my very first NACC conference in 2004, when Linda Hobgood advised me never to use the term “skills” when referring to public speaking. Now, I have the utmost respect for her; I regard Linda and Marlene Preston as the godmothers of the communication centers movement. So I assiduously avoided using “skills,” working off a crib sheet of other terms. It took me literally years to really understand what she was saying (hey, I’m a slow learner!).

The term “skills” connotes a mechanical process, a technical expertise, a dexterity. The term “skills” connotes words as the clothes thoughts put on to go out in (to use a phrase I learned long ago, but can’t remember from whom). The term “skills” connotes behavior that is added on, incidental, after the real work of thinking is completed.

So both those assumptions about how we can just “fix the delivery problems” and those connotations of the term “skills” reveal a simplistic, linear conception of communication. “Just add water” and you’ve got a good speech, right? Wrong!

In communication centers, our goal isn’t better speeches, but better speakers: we know that effective communication is a process—a complex, dynamic, ongoing, challenging, frustrating, rewarding process.

Moreover, it’s a complex process that is integrally related to critical thinking, because it requires audience analysis, research, evaluation and integration of perspectives and concepts, and making decisions about a range of options, including how to (as Wayne Booth put it) enact a rhetorical balance of bringing speaker, audience, and topic together. That’s why so many centers use the rhetorical canons to guide consultations: You can’t solve problems of delivery without attention to invention, disposition, style, and memory!

Communication isn’t (as they say in New Orleans) lagniappe, a nice little addition after the heavy lifting is done. No, communication IS the heavy lifting! In communication centers, we understand what Bob Scott called “rhetoric as epistemic”: that rhetoric is a way of knowing about the world, and an approach to establishing truth.

Now that sounds kinda high-falutin’, so let me share a story from my major advisor at the University of Kansas, Dr. Wil Linkugel. “Kugel,” as I affectionately called him, was a big baseball fan; he even wrote a book about it. He told me about the 3 umpires. The first said, “I call ‘em as they are.” The second said, “I call ‘em as I see ‘em.” The third said, “Whatever I call ‘em, that’s what they are.” That, in a nutshell, is what Scott meant by rhetoric as epistemic: Whatever we call ‘em, that’s what they are to us.

Those of us working in communication centers appreciate Carbaugh and Buzzanell’s point that “knowledge, facts, and perceptions” aren’t “prior to communication” but “social outcomes of communication,” that communication constitutes “a primary social process, . . . the raw stuff of making more than the mere revealing of society” (emphases added).

If, as George Herbert Mead posits, we are “talked into humanity,” then “rhetoric as a critical . . . activity” can and should be deeply connected to rhetoric “as a cultural practice.” The students who visit our centers have the opportunity to better understand this richly complex process of oral communication as a process of intellectual engagement.

Moreover, the students at the center aren’t just those who are our clients: they’re also YOU! As consultants in the center, you appreciate the value of oral communication, in both senses of that phrase. Even more than the students who visit us, you really understand Shachtman when he says that to be articulate requires both “command of the language and ‘the ability to take the perspective of the other person.”

You know, as several of my tutors have told me, that effective mentoring is not a case of top-down instruction, but side-by-side co-creation, where you have to listen closely to what the student says in order to understand both the content meaning and the relationship meaning of the conversation. You demonstrate Aristotle’s concept of ethos in action, building your clients’ sense of your intelligence about the principles and practices of oral communication, your good will in wanting the best for them during their sessions, and your good moral character to establish the necessary trust for a cooperative relationship.

Moreover, you do this over and over again, with a wide variety of individuals, facing a range of challenges, under sometimes trying circumstances. You navigate those times when the clients really don’t want to be there, or want you to write their speech for them, or haven’t prepared, or have “issues” with their group members, or [to borrow a few bon mots] the ones who “know so little and know it so fluently,” or talk so fast they say things they haven’t thought of yet, or have nothing to say and say it endlessly, or . . . or . . . or . . . Fill in the blank! You’ve all had these experiences, and more!

Think about it: Ward and Schwartzman found that communication center coaches learn to engage emotional intelligence, empathy, and trust for effective consultations. And what do these three characteristics constitute? The qualities of leaders. So in the process of advising, you yourself grow, as a student, as a communicator, and as a person.

Now, it isn’t entirely rosy: There are those frustrating sessions to which I referred earlier; and my tutors tell me that once faculty members discover they’re on the Speaking Center staff, their oral communication is held to a higher standard! But because they are smart, they demonstrate a high work ethic, and they “play well with others,” they do indeed “measure up,” on and off campus.

II. Careers

How many of you are seniors? What’s uppermost in your mind? Getting a job. You and those you’ve mentored will take the value of oral communication well beyond campus and into your careers.

You won’t be a bit surprised to learn that the National Communication Association argues that “the ability to explain and condense information is essential for any profession.” Biased we may be, but we’re also right: Survey after survey reveals that the ability to communicate well ranks at or near the top of what employers seek. Every year, polls by the National Association of Colleges and Employers identify “communication ability and integrity as a job seeker’s most important skills and qualities.” “What sets two equally qualified job candidates apart,” NACE notes, “can be as simple as who [is] the better communica[tor].” I would suggest that better communication is far from “simple.”

Another survey of almost 500 companies “found that employers ranked communication abilities first among the desirable personal qualities of future employees.” This result echoes another investigation that found 89% of the employers surveyed ranked ability to communicate effectively, orally and in writing, as essential abilities for their workplaces. I do have to wonder: what the heck are the other 11% thinking??

O’Hair and Eadie discovered that leaders at such organizations as the New York Times, FedEx, and GlaxoSmithKline say communication is vital to their organizations’ success.

In fact, in a recent assessment for the Association of American Colleges and Universities, nearly all those surveyed (93%) agree that “a candidate’s demonstrated capacity to think critically, communicate clearly, and solve complex problems is more important than their undergraduate major.” English or Econ, Classics or Chemistry, the ability to communicate, which entails both critical thinking and problem solving, will stand you in good stead.

Do you believe me yet?

Well, that’s the good news.

The bad news: survey after survey also reveals the ability to communicate well to be at or near the top of what employees lack. Recruiters report serious deficiencies in topic relevance, organization, clarity, and feedback--even though that’s what they most want. Norman Augustine, former Lockheed Martin CEO, argues that to bring our educational system out of the 20th century, “we have to emphasize communication skills, [which we need for] the ability to work in teams and with people from different cultures.”

Having the ability to communicate effectively is especially important in the workplace given that you are likely to hold between 8 and 12 different jobs in your lifetime, not only in different organizations but in entirely different areas.

But I’m an optimist, so let’s go back to the good news: You and those you’ve tutored can make it out there, because of your ability to communicate. I am so proud of what our tutors accomplish not only on campus but also after graduation: They’ve gone to graduate school, veterinary school, nursing school, and seminary; they work in business and journalism, in education and politics and nonprofits (the last after winning the Ms. Wheelchair America contest, with her excellent speech, of course). One works for the American Embassy in Peru; a Spanish major went to China to teach English for a year, and now works for the PGA; another became a counselor in Greece, because she could start a Speaking Center!

Directors, you have your own stories of what your peer consultants have gone on to do: I hope, if you haven’t already, you’ll share those stories with your current crew so they can see the wonderful opportunities that working in your com lab has opened up for them!

So appreciating the value of oral communication is important not only on campus, but also for careers—and in your community.

III. Community

In our increasingly diverse society, in our increasingly global world, we need not only more creative, productive organizations, but also more creative, productive communities. Rod Hart, dean of the Moody College of Communication at the University of Texas, suggests that “some people find it to be in their self-interest to keep others inarticulate.” So by his reckoning, those of us in communication centers are “fundamentally political animal[s].”

What are the implications of communication centers for our communities? Hart posits that the decentralization of rhetorical power challenges “economic, social, and political” “power blocs.” He continues: “When I, as a citizen, learn to use the power of language successfully, I decrease my chances of being victimized by the entrenched, antediluvian forces in my society.”

Those of us in communication centers understand, as a variety of scholars posit, that “communication is the ultimate people-making discipline,” that “facts do not speak; they must be spoken for,” that silence is not golden, that the friends of public speaking are civil discourse and leadership, that the terms “communication” and “community” share the same root: to make common.

We get Deb and Brian McGee’s contention: that “communicative competencies . . . are not merely consistent with democratic practice; instead, the competencies are the enactment of democracy” [emphases added]. So “effective speaking” is “itself a . . . power [and] knowledge necessary” for “democratic citizenship.”

I hope you’re hearing echoes of my earlier point: that rhetoric is epistemic, that of the three umpires, the one who comprehends that “whatever I call ‘em, that’s what they are” is the one with the power.

Conclusion

Let’s face it, Pinker nailed it: we are verbivores! But as verbivores, people too often indulge in junk food.

A colleague of mine observed that we want our students to articulate thoughts. Often, what they provide instead are thoughtlets. And all too frequently, they just blurt out thinkies.

If we in communication centers embrace our calling to help students appreciate the value of oral communication on campus, in careers, and for communities, we can help them turn thinkies into thoughtlets, and thoughtlets into thoughts.

Thank you!

Kathleen J. Turner, Ph.D.

Professor of Communication Studies

Director of Oral Communication

President, National Communication Association